The Quiet Engine in the Basement: Why I Keep Returning to Haruki Murakami

I didn’t ease into Haruki Murakami; I fell down the stairs. I picked up 1Q84 on a whim and came up for air days later—with that particular Murakami afterglow, like you’ve been awake too long inside someone else’s dream. But it wasn’t until Norwegian Wood that I felt seen—really seen. The ache of youth, the shyness that masquerades as detachment, the silent rooms where we store our grief—he wrote those rooms exactly as I remembered them. And The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle did something I’d been circling for years: it gave me permission to write, to really write, to follow a thread down a well and trust that language could be the rope.

That’s the thing about Murakami. He builds a house out of plain sentences—and hides a trapdoor in every room.

The dream logic that doesn’t cheat

Murakami’s magic never feels like an escape hatch. The cats, the wells, the alternate moons, the talking Colonel Sanders—they’re strange, yes, but they behave by the story’s own physics. That’s why I’m hooked: the surreal isn’t decoration; it’s diagnosis. It names hidden systems—loneliness, memory, desire, regret—by letting them walk around in the daylight. The result is a realism that admits how weird ordinary life already is.

Music as blueprint, not soundtrack

Murakami taught me to listen differently. Before him, classical and jazz were moods; after him, they were maps. In his books, a Schubert sonata or a Duke Ellington cut isn’t just background—it’s a tuning fork for the scene. The phrasing of a melody becomes a way to measure time passing in a kitchen, a way to hear a relationship fray, a way to feel a city’s midnight temperature. Reading him made me seek out the records, and the records sent me back to the pages. It’s a circle I’m happy to spin inside.

Loneliness without self-pity

Murakami’s narrators are specialists in being alone. Not the cinematic alone of cigarettes and neon, but the practical kind—empty apartments, dishes in the rack, an evening that needs to be survived. He writes this with enormous mercy. People drift apart. Work numbs you. Love doesn’t fix the shape you carry from childhood. Yet he refuses to sneer at the ordinary or romanticize despair. He doesn’t cure loneliness; he gives it furniture. You can sit down inside it and look around.

Norwegian Wood: the mirror

I met myself in Norwegian Wood. The novel understands how youth can be both feverish and frozen, how desire and duty tangle, how grief becomes a language you accidentally teach the people you love. It’s the first time I felt a writer say, “Yes, that’s how it was,” without a single grand statement. The book is tender where it could be cruel, honest where it could be coy, and its quiet devastations still find me when a certain song comes on.

Wind-Up Bird: the permission slip

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is the novel that moved the furniture in my head. Its calm, almost deadpan sentences guide you into rooms filled with horrors, wonders, and histories that don’t resolve neatly—and that’s the point. It taught me that a writer doesn’t need to explain the mystery; a writer needs to honor it. After reading it, I stopped waiting for a perfect idea and started writing into the imperfect unknown.

Why you should read him

Plain style, deep waters. The language is simple enough to disappear; what’s left is feeling, and the eerie clarity that follows it.

Emotional accuracy. He names the weather of being human—especially the drafty corners we avoid—without melodrama.

Worlds that stay with you. Walk through one of his doors and the hallway lingers for years.

Art that cross-pollinates. If you love music, you’ll hear more; if you don’t yet, you will.

Courage for the ordinary. He treats cooking pasta, folding laundry, feeding a cat like rituals that hold the day together—and sometimes, they do.

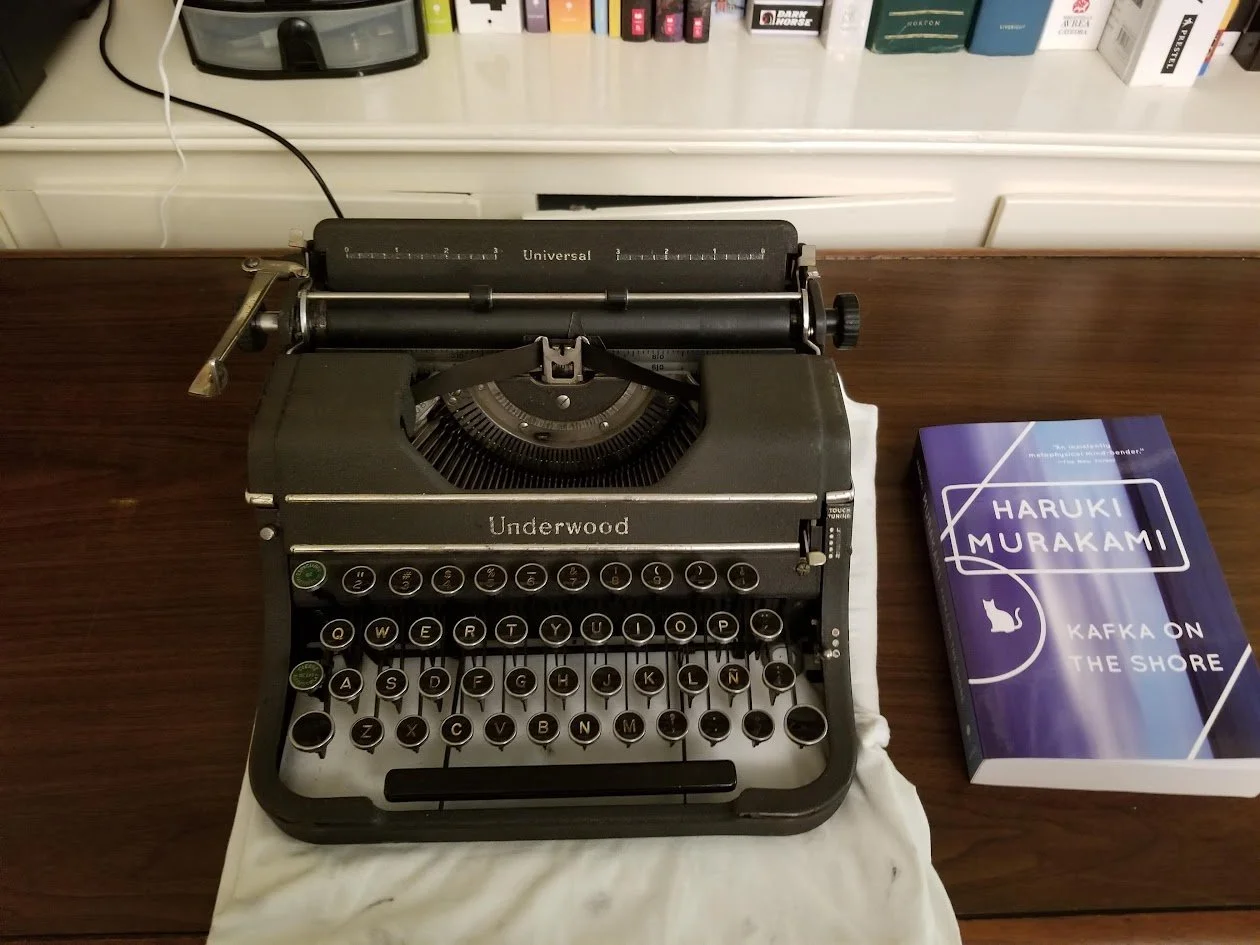

Where to start (and how to keep going)

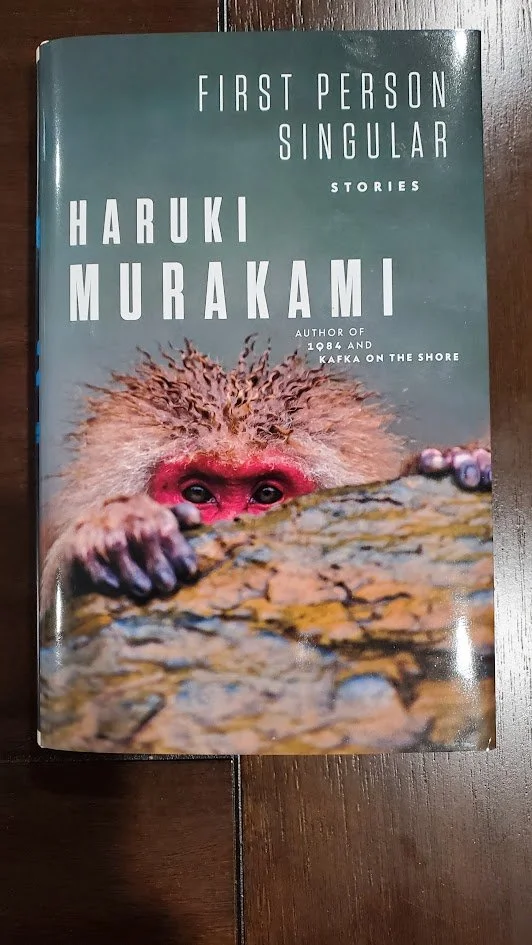

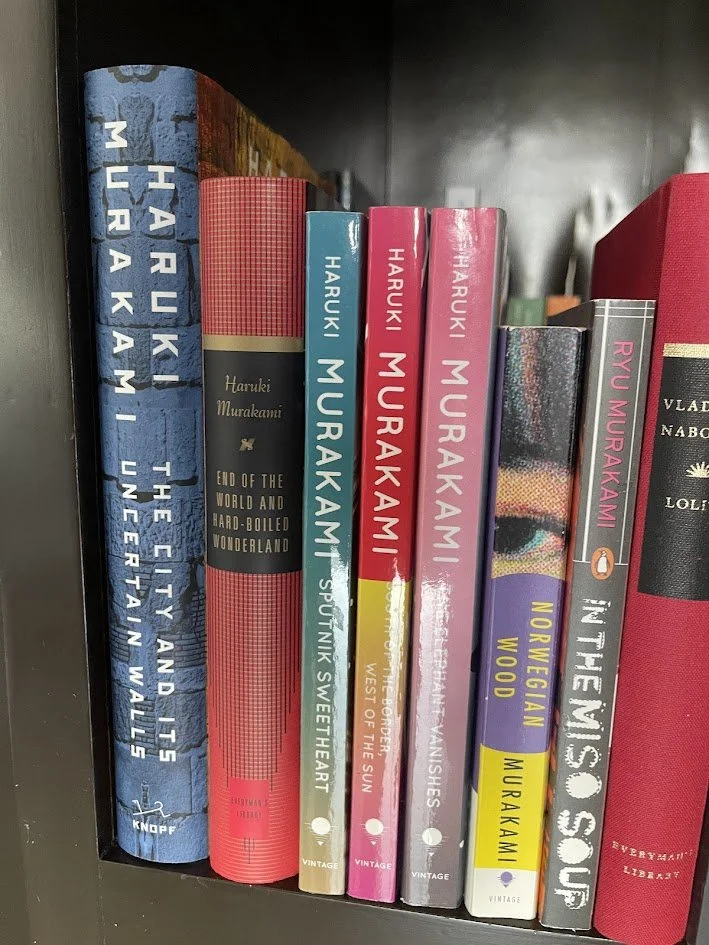

If you’re me, you begin with 1Q84 because you like big swings. Then you read Norwegian Wood and realize the small swing can knock the wind out of you. After that, dive into The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and let it teach you to live with mystery. Round it out with Kafka on the Shore to feel how prophecy and adolescence share a room, and then roam: A Wild Sheep Chase, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Men Without Women. Order matters less than the rhythm you make with the books and whatever record you put on while you read.

Murakami didn’t save me, change me, or fix me. He gave me company. He made my solitude feel less like failure and more like a country where I could learn the language. He reminded me that we can love the strange without abandoning the simple, that we can cook dinner and still talk to the moon. That’s why I love his work. That’s why I keep devouring it. And that’s why I think you should walk through one of his doors and see what changes in your house.